Europe after the First World War

The victors of the First World War agreed upon post-war Europe in negotiations held in Paris. These negotiations resulted in five peace treaties. Their objective was to establish nation states. Compromises and the unusual conditions meant that unresolved national disputes still remained between various countries. Despite this, for Europe in particular the negotiations in Paris were followed by a period of more than ten years where numerous international agreements were made for the purpose of outlawing wars of aggression and maintaining permanent peace.

Peace treaties of the First World War

The principles of the world order after the First World War were decided upon in a meeting of the Allied victors that opened in Paris in January 1919. It was attended by representatives from 27 nations. In practice, the agreements were drawn up between the representatives of four powers: the United States of America, the United Kingdom, France and Italy. The group was led by President Woodrow Wilson of the United States. The United Kingdom was represented by Prime Minister Lloyd George, France by Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau and Italy by Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando.

The Allied victors signed four peace treaties in 1919 and the fifth with the Ottoman Empire in 1920. The other peace treaties were signed with Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria and Germany. The peace treaties were named after suburbs of Paris, with the exception of the treaty signed with Germany, which was named after the Palace of Versailles, where it was signed.

New European states

The peace treaties confirmed the dissolution of three empires: Austria-Hungary, the German Empire and the Russian Empire. The final struggle of the fourth empire, the Ottoman Empire, which had fought by Germany’s side in the First World War, ended during the Turkish War of Independence (1919–23). The Republic of Turkey was established on 29 October 1923. The new independent states of Europe were: Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Austria-Hungary was also divided into two independent states.

A key objective of the Paris peace treaties in drawing new national boundaries was to follow the principle of national self-determination. The aim was to draw the national boundaries based on a common language. However, the resulting peace treaties included several exceptions to this principle. Several states retained large linguistic minorities which would have liked to belong to the state where their own language was spoken.

In Germany, the peace treaty was considered to be humiliating

Germany did not want to sign its peace treaty, but having lost the war, it had no other choice. Germany felt that the boundaries established by its peace treaty and the limitations imposed on the country, for example with regard to its military, were unjust. In the eastern part of Germany, Posen and West Prussia were annexed to Poland. The old German city of Danzig became a free city that belonged to no state. Border arrangements cut off Germany’s road connections to East Prussia, which remained a part of Germany, and Lithuania annexed the Memel Territory, which formerly belonged to Prussia. The population of the rural areas surrounding the German city was primarily Lithuanian. The victorious states had planned to leave the matter to the League of Nations.

League of Nations

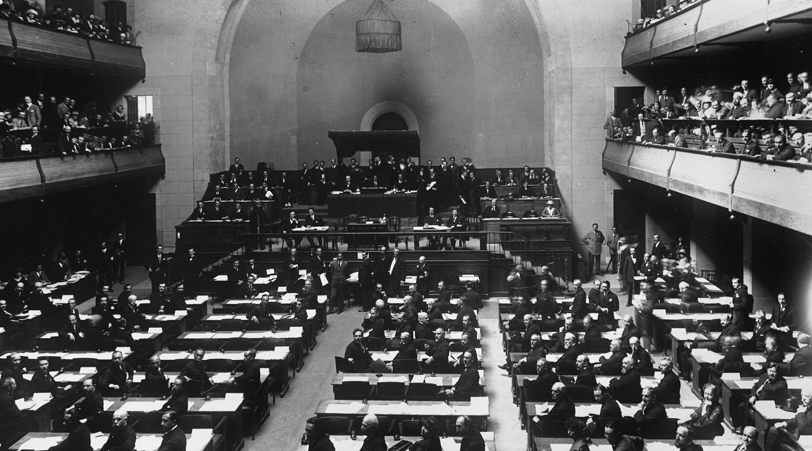

A conference of the League of Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1921. Image: Harlingue/Roger Viollet/Getty Images.

The Covenant of the League of Nations was appended to the peace treaty signed with Germany. The strongest driving force behind the founding of the League of Nations was President Woodrow Wilson of the United States. He saw the new organisation as a peaceful arbiter of international conflicts. Wilson believed that the organisation would also be able to fix the shortcomings that were apparent in the peace treaties as a result of compromises.

The first General Assembly of the League of Nations was held in Geneva on 15 November 1920. The United States never joined the organisation. Germany was accepted as a member of the League of Nations in 1926. The Soviet Union considered the League of Nations to be a coalition of capitalist countries. However, in the 1930s the Soviet Union was ready to join the League of Nations and was accepted as a member in 1934.

The Åland Islands dispute in the League of Nations

The League of Nations settled the dispute between Sweden and Finland over the Åland Islands in Finland’s favour. The settlement included a convention regarding the demilitarisation and neutralisation of the Åland Islands, known as the Åland Convention. It was signed on 20 October 1921. Finland ratified the convention on 28 January 1922. The instrument of ratification was deposited in Geneva on 6 April 1922. The Russian SFSR, which was not a member of the League of Nations, was not included in the signatory states of the convention. The new convention supplemented the Åland Convention of 1856, signed between France, the United Kingdom and Russia on 30 March 1856.

Poland retained Vilnius

The newly independent Poland and Lithuania were still in a dispute over the city of Vilnius and the surrounding area. According to the census of 1916, a little over half of the population of the city of Vilnius were native speakers of Polish (54.7%). Jews formed the second largest population group (41.5%). Poland retained the city and its surrounding areas.

Ari Raunio

SUOMEKSI

SUOMEKSI PÅ SVENSKA

PÅ SVENSKA по-русски

по-русски