Independent Finland in Europe

Finland’s relationship with the Soviet Union, the successor state of Finland’s former mother country, was problematic. Finland wanted to gain possession of the home region of the Karelians in Russia. Russia’s other neighbouring countries in the west shared Finland’s fear that the Soviet Union would try to re-establish the borders of the Russian Empire. However, Finland did not want to participate in the alliance led by Poland. It would have risked Finland getting involved in a conflict between Poland and the Soviet Union. Finland tried to establish a different agreement system with the Soviet Union than the USSR’s other neighbouring countries.

Russia launched the Russification of the Grand Duchy of Finland in the late 19th century

Russia’s Russification policy of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was oppressive for the Grand Duchy of Finland. The Grand Duchy of Finland was a former eastern part of Sweden, which had been annexed to Russia in 1809 but allowed to retain its own religion and laws, among other things. The imperial manifesto issued in February 1899 was considered to repeal the Swedish form of government of 1772, which was still in effect in Finland at the time. In 1901, Russia dissolved the Finnish Army, which had been formed in the early 1880s. The Conscription Act had been passed in 1878. The Finnish Military Academy was abolished in 1903, and the Guard of Finland was abolished as the last brigade-level unit in 1905.

The military education of Finns began in Germany in 1914, leading to the birth of the Jaeger Movement

Strong resistance movements arose in Finland. The objective of one of them was for Finland to break away from Russia, by force if necessary. The supporters of this movement felt that the major European war that had begun in 1914 provided a good opportunity for this. An uprising would require military leaders, who would have to be trained abroad. Germany agreed to this. This marked the birth of the Jaeger Movement. Almost 1,900 men left for military training in Germany between 1915 and 1917.

Finland declared its independence on 6 December 1917

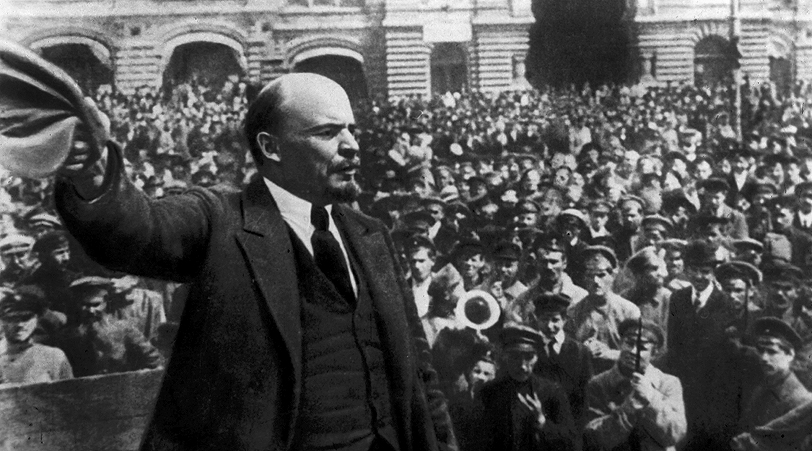

Lenin giving a speech at Red Square in Moscow in October 1917. Image: Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images.

The Bolsheviks rose to power in Russia in the October Revolution of 1917. The Grand Duchy of Finland separated from Russia after the revolution by declaring its independence on 6 December 1917. The Bolshevik Russian SFSR recognised Finland’s independence in January 1918. At the end of the same month, the radical wing of the Finnish labour movement launched its own revolution. The Russian SFSR supported the revolutionaries and did not expedite the withdrawing of its troops from Finland. On the first day of the revolution, the government troops began disarming the Russian troops within their territories.

The freedom war that was a civil war

The map above shows the division of Finland between southern Finland, which was controlled by the revolutionaries, known as the Reds, and the rest of Finland, which was controlled by the government, i.e. the Whites. Both territories included individual localities controlled by the opposition.

The map above shows the division of Finland between southern Finland, which was controlled by the revolutionaries, known as the Reds, and the rest of Finland, which was controlled by the government, i.e. the Whites. Both territories included individual localities controlled by the opposition.

The government troops of the Civil War comprised Civil Guards, recruited troops and conscripts. Swedish volunteers also participated in the war. The almost 1,300 Jaegers who arrived in Finland played a key role in the conscript troops formed during the war as trainers and leaders of the battalion and its subordinate troops. The revolutionary forces were formed by the Red Guards. The revolutionaries had practically no personnel with military training.

During the war of 1918, Finland disarmed the Russian soldiers within its territory. However, all actual battles were fought against Finland’s own citizens who had started the revolution. This war, which became a civil war, ended in May 1918 in the victory of the government troops, which were supported by Germany. The German Baltic Sea Division also participated in the war.

The revolutionaries were defeated over the course of May. Some of the revolutionaries were able to escape to the Russian SFSR. There they established the Communist Party of Finland (SKP). In Finland, communist activities were banned.

Short period of pro-German policy

Lieutenant General Mannerheim (general of the cavalry as of 7 March 1918), who had been appointed by the government as commander-in-chief of its troops before the Civil War, resigned four days after the victory parade held in Helsinki on 16 May 1918. He did so in protest of the government’s decision to follow Germany’s instructions on developing the Finnish Army. Finland’s First World War-era pro-German policy culminated in the selection of a German prince as the King of Finland.

K. J. Ståhlberg became president in July 1919

President of the Republic K. J. Ståhlberg has just arrived in Suomenlinna in the early 1920s. Image: Military Museum.

President of the Republic K. J. Ståhlberg has just arrived in Suomenlinna in the early 1920s. Image: Military Museum.

After Germany lost the world war, a change of government took place in Finland. Finland abandoned its pro-German stance and sought approval from the West. In December 1918, Mannerheim was appointed as regent of Finland. Instead of a kingdom, Finland became a republic. The parliament elected the nation’s first president in July 1919. The main candidates who ran in the election organised by the parliament were Mannerheim and K. J. Ståhlberg. The latter received 143 of the 197 votes cast, while Mannerheim received 50 votes. After the election, Mannerheim withdrew from public life.

Kinship Wars

Since the very start of its independence, Finland wanted to gain possession of the Russian territory of East Karelia, which was populated by Karelians. In 1919, the Finnish government and parliament approved the operations of military expeditions by Finnish volunteers in East Karelia. The Finnish government unofficially supported Russian counter-revolutionaries in White Sea Karelia, even after Finland and the Russian SFSR signed the Treaty of Tartu in October 1920. In February 1922, the Russian SFSR’s troops defeated the uprising in White Sea Karelia and the Finnish voluntary troops who had rushed to aid it. Finland and the Russian SFSR signed an agreement on the inviolability of their border in Moscow on 1 June.

Finland rejected an agreement with the Russian SFSR’s western neighbouring countries in 1922

One important factor in Finland’s search for a foreign policy orientation was obtaining support against the Russian SFSR (later the Soviet Union), which was considered to be the greatest threat against Finland’s independence. The assessment was that the Russian SFSR would seek to re-establish the borders of the Russian Empire. This fear was shared by the other nations that had separated from Russia – Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. However, Lithuania did not work in close cooperation with the rest of these western neighbouring countries. In the aftermath of the First World War, Poland had annexed the city of Vilnius, which Lithuania had wanted to establish as its capital, as well as its surroundings.

In May 1922, the Finnish Parliament rejected the proposal prepared by the government for a political cooperation agreement with the Russian SFSR’s other neighbouring countries. This decision was based on a fear that Finland would become involved in possible conflicts, particularly between Poland and the Russian SFSR. The war between the Russian SFSR and Poland that had started after the First World War had ended in 1921.

The Soviet–Finnish Non-Aggression Pact was signed in 1932

The Soviet Union sought to secure its western border from possible attacks by the United Kingdom or France by signing agreements with its neighbouring countries. Finland wanted to stay out of such an agreement system. Despite this, Finland entered into a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union in 1932.

Finland declared itself to be a Nordic country in 1935

In July 1933, Finland announced its intention to join the Convention for the Definition of Aggression that had been signed in London. The convention entered into force in February 1934, after the deposition of the instrument of ratification. Drafted at the Soviet Union’s initiative, the convention was intended to supplement the Kellogg–Briand Pact, which forbade warfare. The following year, Finland declared its goal to be to adopt a pro-Nordic policy, as it wanted to identify itself with the Scandinavian countries.

Ari Raunio

SUOMEKSI

SUOMEKSI PÅ SVENSKA

PÅ SVENSKA по-русски

по-русски